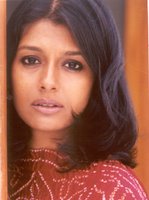

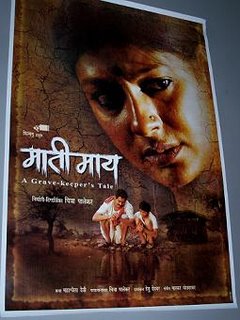

Not much to add this time around; more frantic speed-walking back and forth across the city, attempting to join ticket-holder lineups before they begin to dangerously swell and overfill. More money wasted on junk food and sugary, caffeinated Starbucks drinks to keep myself awake through the waiting and watching (yes, I did pack a lunch in an effort to conserve funds, but I ate it for breakfast. Ah well.) No celebrity sightings for the first three films (the lead actress of Climates, Ebru Ceylan, showed up but the lighting was too poor to take shots - I also hated the film, so no big loss); as for A Grave-Keeper's Tale, it was a true joy to have director Chitra Palekar and the gifted actor Nandita Das (you may recall that she served on the Cannes Film Festival jury last year) present to both introduce the film and participate in a Q&A following the screening. I had a chance to briefly greet Das afterwards and congratulate her on the strength of her past performances (in Fire, Bawandar, Hari-Bhari, Kannathil Muthamittal, etc) and her work in this film. I am still a little star-struck, to tell you the truth.

Not much to add this time around; more frantic speed-walking back and forth across the city, attempting to join ticket-holder lineups before they begin to dangerously swell and overfill. More money wasted on junk food and sugary, caffeinated Starbucks drinks to keep myself awake through the waiting and watching (yes, I did pack a lunch in an effort to conserve funds, but I ate it for breakfast. Ah well.) No celebrity sightings for the first three films (the lead actress of Climates, Ebru Ceylan, showed up but the lighting was too poor to take shots - I also hated the film, so no big loss); as for A Grave-Keeper's Tale, it was a true joy to have director Chitra Palekar and the gifted actor Nandita Das (you may recall that she served on the Cannes Film Festival jury last year) present to both introduce the film and participate in a Q&A following the screening. I had a chance to briefly greet Das afterwards and congratulate her on the strength of her past performances (in Fire, Bawandar, Hari-Bhari, Kannathil Muthamittal, etc) and her work in this film. I am still a little star-struck, to tell you the truth.Note: I'm not really happy with the state of these reviews, as they were worded quite differently (read: better) in my mind on the way home, but they will have to do for now. I have to wake up in less than five hours to head back in an attempt to grab tickets for Almodóvar's Volver. Wish me luck (if you will be so kind.)

Takashi Miike’s latest, Big Bang Love, Juvenile A, is a fascinating blend of philosophical treaty, murder mystery and unrequited gay romance. While it manages to successfully encompass and pull off all those elements in varying degrees, it cannot be denied that the film is a love-it-or-hate-it experience. This is perhaps the first festival screening I can remember where absolutely no one clapped - for a Toronto audience, that is virtually unheard of. Even for films that are largely met with an air of indifference, smatterings of applause here and there are typical (even expected.) The gist of the matter involves two young men - Jun and Shiro - recently imprisoned for unrelated acts of murder; the first is a soft-spoken, boyish youth, the latter a wild and dangerous troublemaker. The film begins with the discovery of Shiro's body being strangled at the hands of Jun, and the majority of the film is then devoted to flashbacks, in which Miike depicts each youth's troubled backstory and the experiences they have in prison (with each other, and with other individuals populating the rank and cavernous building.) Miike also explores the notion of manhood and identity, and he returns to these matters continuously throughout. Much time is also devoted to a thread involving an inquisitive police official attempting to solve the mystery behind Shiro's end (confessionals by the inmates, warden and other staff are directed towards the camera, as if the audience members are the ones positing the questions.) For the most part, Big Bang Love works; the creepy atmosphere, symbolic imagery (both men are able to look beyond the prison walls and observe a rocket and Mayan pyramid, representing space to one, and heaven to the other), and the time shifts are engaging and maintain interest. Unfortunately, the proceedings run out of steam about two-thirds in; Miike spends more time re-visiting what already came before in the murder investigation, while more pressing matters (such as the complexity of Jun and Shiro's intense bond) are left behind. I did enjoy most of it, but am unsure to what extent I would recommend it to others. C+

Takashi Miike’s latest, Big Bang Love, Juvenile A, is a fascinating blend of philosophical treaty, murder mystery and unrequited gay romance. While it manages to successfully encompass and pull off all those elements in varying degrees, it cannot be denied that the film is a love-it-or-hate-it experience. This is perhaps the first festival screening I can remember where absolutely no one clapped - for a Toronto audience, that is virtually unheard of. Even for films that are largely met with an air of indifference, smatterings of applause here and there are typical (even expected.) The gist of the matter involves two young men - Jun and Shiro - recently imprisoned for unrelated acts of murder; the first is a soft-spoken, boyish youth, the latter a wild and dangerous troublemaker. The film begins with the discovery of Shiro's body being strangled at the hands of Jun, and the majority of the film is then devoted to flashbacks, in which Miike depicts each youth's troubled backstory and the experiences they have in prison (with each other, and with other individuals populating the rank and cavernous building.) Miike also explores the notion of manhood and identity, and he returns to these matters continuously throughout. Much time is also devoted to a thread involving an inquisitive police official attempting to solve the mystery behind Shiro's end (confessionals by the inmates, warden and other staff are directed towards the camera, as if the audience members are the ones positing the questions.) For the most part, Big Bang Love works; the creepy atmosphere, symbolic imagery (both men are able to look beyond the prison walls and observe a rocket and Mayan pyramid, representing space to one, and heaven to the other), and the time shifts are engaging and maintain interest. Unfortunately, the proceedings run out of steam about two-thirds in; Miike spends more time re-visiting what already came before in the murder investigation, while more pressing matters (such as the complexity of Jun and Shiro's intense bond) are left behind. I did enjoy most of it, but am unsure to what extent I would recommend it to others. C+ *Possible Spoilers* Beginning early on in the familiar convention of a gripping film noir (all the ingredients are present, from the gorgeous femme fatale, to the moody and dense atmosphere), Finnish director Aki Kaurismäki’s Lights in the Dusk surprisingly transitions into something of a bleak existential drama about trying to make it day by day in an unsympathetic, self-interested world. At first, the shift may seem jarring and at odds with what came before (especially considering the director's focus during the first hour of running time.) But upon further reflection, it is arguable that the tragic ordeals the lead character Koistenen experiences (played by a pitiable Janne Hyytiäinen) are part of an attempt by Kaurismäki to drive home an ironic twist on the expected outcome. This, in my mind, elevates the film from a standard crime potboiler into something much more soulful and character-driven. The basic premise involves an introspective, people-shy security guard who finds any type of human interaction painful to sustain. His social life remains empty and bland until a friendly blonde walks into his life and opens him up to the possibility of an intimate connection. But what follows is an utter and complete downfall from (comfortable, if unsatisfying) stability; Koistenen quickly finds himself in hot water, and his situation progressively worsens from one scene to the next. On one hand, his refusal to challenge and fight back against his oppressors is frustrating; even when he does decide to retaliate, he surges forward half-heartedly, as if he knows that failure is inevitable. And yet, this is not a revenge drama - Kaurismäki is more interested in the character's up-and-down journey, and the small - often fleeting - pockets of hope that give him purpose to move on (including Maria Heiskanen's Aila, an old friend who hints at wanting more.) It is a quiet, meditative film, but a character journey well worth undertaking. B

*Possible Spoilers* Beginning early on in the familiar convention of a gripping film noir (all the ingredients are present, from the gorgeous femme fatale, to the moody and dense atmosphere), Finnish director Aki Kaurismäki’s Lights in the Dusk surprisingly transitions into something of a bleak existential drama about trying to make it day by day in an unsympathetic, self-interested world. At first, the shift may seem jarring and at odds with what came before (especially considering the director's focus during the first hour of running time.) But upon further reflection, it is arguable that the tragic ordeals the lead character Koistenen experiences (played by a pitiable Janne Hyytiäinen) are part of an attempt by Kaurismäki to drive home an ironic twist on the expected outcome. This, in my mind, elevates the film from a standard crime potboiler into something much more soulful and character-driven. The basic premise involves an introspective, people-shy security guard who finds any type of human interaction painful to sustain. His social life remains empty and bland until a friendly blonde walks into his life and opens him up to the possibility of an intimate connection. But what follows is an utter and complete downfall from (comfortable, if unsatisfying) stability; Koistenen quickly finds himself in hot water, and his situation progressively worsens from one scene to the next. On one hand, his refusal to challenge and fight back against his oppressors is frustrating; even when he does decide to retaliate, he surges forward half-heartedly, as if he knows that failure is inevitable. And yet, this is not a revenge drama - Kaurismäki is more interested in the character's up-and-down journey, and the small - often fleeting - pockets of hope that give him purpose to move on (including Maria Heiskanen's Aila, an old friend who hints at wanting more.) It is a quiet, meditative film, but a character journey well worth undertaking. B I am not sure what director/actor/writer/editor Nuri Bilge Ceylan’s intention was with the interminable Climates; whether a narcissistic vanity project or an effort to exorcise his own personal demons, it is a bloated misfire by any definition. Attempting to portray the breakdown – and then the potential rekindling – of a strained marriage, the film demands an hour and forty minutes to cover barely twenty minutes’ of action. The conceit is that the stages of the relationship are mirrored in the shifting seasons – spring/summer (growth), autumn (slow decay) and winter (death.) Ceylan’s metaphors seem absolutely novel compared to his hollow script, which offers nothing for the viewer to mull upon. His approach is restricted to achingly long takes, where dramatic beats punctuated in between dialogue are made to signify severity. The reality is that there is no pay-off; Ceylan repeats the same cycle of connection and misunderstanding between the husband and wife incessantly, with nothing new to offer. Ceylan and Ebru Ceylan (as the conflicted woman; also the director’s off-screen wife) commit themselves fully to recreating what are no doubt very personal family histories, but they are undoubtedly events better off left in memory. The different “climates” and places depicted – a beach paradise getaway in Kas, the snowy mountain ranges of the north – attempt to add dimension, but serve simply as distractions from the weakly-etched characters always undermining themselves. The saving grace of the film comes in the appearance of actor Nazan Kesal, playing a scornful ex-flame of Ceylan’s; working with nothing substantial, she conveys a palpable mix of bitterness, lust and hesitance in her interludes with Ceylan – it is a shame that she only appears in the second act. The film could have used her energy during the turgid majority. D-

I am not sure what director/actor/writer/editor Nuri Bilge Ceylan’s intention was with the interminable Climates; whether a narcissistic vanity project or an effort to exorcise his own personal demons, it is a bloated misfire by any definition. Attempting to portray the breakdown – and then the potential rekindling – of a strained marriage, the film demands an hour and forty minutes to cover barely twenty minutes’ of action. The conceit is that the stages of the relationship are mirrored in the shifting seasons – spring/summer (growth), autumn (slow decay) and winter (death.) Ceylan’s metaphors seem absolutely novel compared to his hollow script, which offers nothing for the viewer to mull upon. His approach is restricted to achingly long takes, where dramatic beats punctuated in between dialogue are made to signify severity. The reality is that there is no pay-off; Ceylan repeats the same cycle of connection and misunderstanding between the husband and wife incessantly, with nothing new to offer. Ceylan and Ebru Ceylan (as the conflicted woman; also the director’s off-screen wife) commit themselves fully to recreating what are no doubt very personal family histories, but they are undoubtedly events better off left in memory. The different “climates” and places depicted – a beach paradise getaway in Kas, the snowy mountain ranges of the north – attempt to add dimension, but serve simply as distractions from the weakly-etched characters always undermining themselves. The saving grace of the film comes in the appearance of actor Nazan Kesal, playing a scornful ex-flame of Ceylan’s; working with nothing substantial, she conveys a palpable mix of bitterness, lust and hesitance in her interludes with Ceylan – it is a shame that she only appears in the second act. The film could have used her energy during the turgid majority. D- For a first attempt with a full-length feature film, Chitra Palekar truly impresses with A Grave-Keeper's Tale, based on a short story by celebrated Bengali writer Mahasweta Devi. Set in a post-Gandhi, late 1950's Maharashtra village, it is a film that critically examines the state of (especially) women under caste and gender hierarchies. However, Palekar is also interested in how power imbalances created by ignorance and superstition become internalized and fixed within the consciousness of a people carrying generations of abuse and inequality. The gifted Nandita Das, one of India's best actors working today outside the mainstream output, plays a frightful village outcast denounced as a "ghoul" that feeds and nurtures of the bodies of dead young children. The villagers make sure to keep their distance, lest the witch pollute their environments with her evil and unlucky presence. Dalits (or "untouchables") themselves are unsympathetic to her situation; as one woman puts it, "I may be an untouchable, but at least I do not bury the bodies of dead children." Indeed, Chandi is left the task of performing funeral rites for young ones, a responsibility left to her by her ancestors. While the status quo maintains that Chandi live a separate life from her fellow people (even her close relations), a young boy fascinated by her infamous reputation decides to ask his father about the intimidating figure. What follows is a detailed backstory of the "witch", once a mother and integral part of the community, and the events causing downfall into ill-repute. Palekar's film has its usual hiccups (easily forgivable, considering the minimal budget and it being her first effort), but the passion for the issues is potent. When Chandi refuses to be complicit in the village men's demands or stay confined in the community's definition of a "good woman", she is punished with a brutal sentence. Palekar also shows how Chandi's husband (the wonderful Atul Kulkarni) also turns against her when he feels the judgment and disapproval of his fellow villagers. It is a simple film, but is moving in its universal ideas about mothers and children, conformity in society, and the need to isolate and suppress what is different from the "norm". B

For a first attempt with a full-length feature film, Chitra Palekar truly impresses with A Grave-Keeper's Tale, based on a short story by celebrated Bengali writer Mahasweta Devi. Set in a post-Gandhi, late 1950's Maharashtra village, it is a film that critically examines the state of (especially) women under caste and gender hierarchies. However, Palekar is also interested in how power imbalances created by ignorance and superstition become internalized and fixed within the consciousness of a people carrying generations of abuse and inequality. The gifted Nandita Das, one of India's best actors working today outside the mainstream output, plays a frightful village outcast denounced as a "ghoul" that feeds and nurtures of the bodies of dead young children. The villagers make sure to keep their distance, lest the witch pollute their environments with her evil and unlucky presence. Dalits (or "untouchables") themselves are unsympathetic to her situation; as one woman puts it, "I may be an untouchable, but at least I do not bury the bodies of dead children." Indeed, Chandi is left the task of performing funeral rites for young ones, a responsibility left to her by her ancestors. While the status quo maintains that Chandi live a separate life from her fellow people (even her close relations), a young boy fascinated by her infamous reputation decides to ask his father about the intimidating figure. What follows is a detailed backstory of the "witch", once a mother and integral part of the community, and the events causing downfall into ill-repute. Palekar's film has its usual hiccups (easily forgivable, considering the minimal budget and it being her first effort), but the passion for the issues is potent. When Chandi refuses to be complicit in the village men's demands or stay confined in the community's definition of a "good woman", she is punished with a brutal sentence. Palekar also shows how Chandi's husband (the wonderful Atul Kulkarni) also turns against her when he feels the judgment and disapproval of his fellow villagers. It is a simple film, but is moving in its universal ideas about mothers and children, conformity in society, and the need to isolate and suppress what is different from the "norm". B

4 comments:

I'm seriously loving these reviews, even if I hadn't heard of half these films.

Good luck with "Volver"!!! I'll trust you'll love it!

Oh my God, you saw it!!!

AND loved it. Fantastic!

Whoa, you're fast! Review should be up in a couple of hours.

Terrific reviews! So glad I found your blog; will bookmark and vist again.

Post a Comment