* Click the above link to direct yourself back to Nathaniel R's Pfeiffer blog-a-thon hub. And please note, the following "review" has major spoilers, so beware.

Quite frankly, you can all keep your Jamie Lee Curtises, Neve Campbells, and Jennifer Love Hewitts (I have a feeling that there will be few takers for that last one). I have found my absolute Scream Queen in the form of Michelle Pfeiffer in Robert Zemeckis's über-underrated Hitchcokian throwback Wh

at Lies Beneath, a film that had me screaming like a five-year-old and covering my eyes both times I saw it in theatres (something that has happened during only two other films - The Blair Witch Project and The Others.) I have to admit that before falling in love with this performance, I was not particularly ga-ga over the actress overall. You must consider that I was a naïve sixteen-year-old, only familiar with her work in the lacklustre vehicle Dangerous Minds and her respectable appearance in A Midsummer Night's Dream. But nothing prepared me for Pfeiffer in this film; even if you are a non-fan of the special effects extravaganza as a whole (and there are many of you out there), I doubt you can find much to quibble with in her luminous performance. What is so riveting about Pfeiffer's portrayal of this fractured, over medicated soul is that we are invited to piece together the mystery together along with her. But her neurotic Nancy Drew never grates on the nerves; rather, because she so desperately makes conclusions on such contradictory and shadowy evidence, we are thusly just as bewildered, clueless and scared shitless as she is.

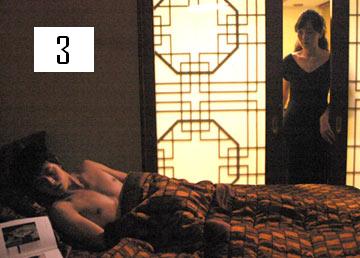

at Lies Beneath, a film that had me screaming like a five-year-old and covering my eyes both times I saw it in theatres (something that has happened during only two other films - The Blair Witch Project and The Others.) I have to admit that before falling in love with this performance, I was not particularly ga-ga over the actress overall. You must consider that I was a naïve sixteen-year-old, only familiar with her work in the lacklustre vehicle Dangerous Minds and her respectable appearance in A Midsummer Night's Dream. But nothing prepared me for Pfeiffer in this film; even if you are a non-fan of the special effects extravaganza as a whole (and there are many of you out there), I doubt you can find much to quibble with in her luminous performance. What is so riveting about Pfeiffer's portrayal of this fractured, over medicated soul is that we are invited to piece together the mystery together along with her. But her neurotic Nancy Drew never grates on the nerves; rather, because she so desperately makes conclusions on such contradictory and shadowy evidence, we are thusly just as bewildered, clueless and scared shitless as she is.But as effective as Pfeiffer is at jumping, screaming and apprehensively peeking around corners, what I love most about her portrayal are the funny, seemingly small elements. Take for instance her playful attempts early on in the film to seduce her husband Norman (Harrison Ford) away from his consuming work ("Ooh, a couple of Swedish sailor cells just gang-divided a virginal cheerleader cell...") , and the delightfully naughty gaze that follows thereafter. Or her f

rantic line delivery of "Fashionably five minutes late!!!", throwing her arms wildly in the air when informed by Norman that they will be tardy for a dinner with friends because of her compulsive neighbour-spying. One of my favourite moments is how she responds to her very kooky neighbour's ridiculous question ("Have you ever felt so completely consumed by a feeling for someone that you couldn't breathe?") with a wavering "Umm... sure". Hysterical! And, of course, she delivers in spades during the hard-hitting, emotional scenes. Recall how genuinely believable her plight is - when she matter-of-factly states to her therapist "There's a ghost in my house", you believe her (and not just because you were there during the hauntings). And then there's her stellar depiction of unwelcome memories suddenly returning ("I remember the party... oh god") - you can literally see the images re-enter her brain, weighing her down. I am sitting here with my notes, and every line is a reference to a particular nuance or detail in her performance (read: I could go on for hours citing these examples).

rantic line delivery of "Fashionably five minutes late!!!", throwing her arms wildly in the air when informed by Norman that they will be tardy for a dinner with friends because of her compulsive neighbour-spying. One of my favourite moments is how she responds to her very kooky neighbour's ridiculous question ("Have you ever felt so completely consumed by a feeling for someone that you couldn't breathe?") with a wavering "Umm... sure". Hysterical! And, of course, she delivers in spades during the hard-hitting, emotional scenes. Recall how genuinely believable her plight is - when she matter-of-factly states to her therapist "There's a ghost in my house", you believe her (and not just because you were there during the hauntings). And then there's her stellar depiction of unwelcome memories suddenly returning ("I remember the party... oh god") - you can literally see the images re-enter her brain, weighing her down. I am sitting here with my notes, and every line is a reference to a particular nuance or detail in her performance (read: I could go on for hours citing these examples).But what really seals the deal for me here is the way in which she remarkably holds the film together when it starts to unravel at an alarming rate into plain silliness. Who else could take potential howlers like "Forbidden fruit. You gotta problem with that?" and make them sound credible? It certainly helps that Pfeiffer has had experience playing possessed or similarly... intense characters (Catwoman), because the script's unnecessary shift in this regard ("I think she's starting to suspect something") is unfortunate. One scene that I cannot stop thinking about is in the final act, in which Pfeiffer is able to communicate such terror despite having her motor skills temporary impaired and her face completely frozen during that tortuous bathtub showdown. Just look at how she conveys tragic, bone-chilling desolation through only her eyes and a shivery release of breath when Norman brutally offers, "I'm sure, in some tragic way, your suicide is gonna help bring Caitlin and I closer together". Wowza. At times, I wish I could include clips from the film here to demonstrate my points... but you'll have to take my word for it. ;) I have no reservations in stating that this is one of my favourite performances by an actor - ever.

Anyways, I extend my best wishes to you, Ms. Pfeiffer, for a most wonderful Birthday and an even better year to come (both in terms of your personal and "reel" lives). Please do not stop making movies - I cannot promise that Oscar will finally be yours (you certainly deserved to be in contention for this performance, especially considering your limp competition), but all of us will be there to cheer you on and worship the ground you walk on. Happy Birthday!